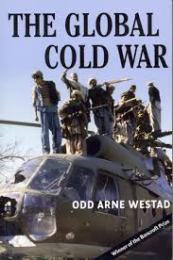

In my last post I outlined historian Odd Arne Wested’s argument for the ideological foundations of American policy during the Cold War. Unlike earlier generations of Cold War historians he places American Cold War policies in the the context of a long history of territorial expansion based on an ideology of progress with the US as uniquely qualified to export the first political system based on scientific principles. These principles were founded on individualism and the centrality of the market. On this basis, Wested emphasizes a line of thinking coupled with foreign intervention that runs from Jefferson’s Barbary Wars of the early 19th century through the occupation of the Philippines in the 1890s to the quagmire of the American war in Vietnam during the 1960s and 1970s.

Marx, Engels, Lenin: the personification of Marxism-Leninism, the universalist ideology of the Soviet version of modernity.

He takes a parallel tack in addressing the roots of Soviet thinking during the Cold War and Soviet foreign interventions, particularly in the Third World. In both cases, policies were inspired by ideologies related to historical missions each state took upon itself for the (presumed) welfare of societies everywhere.

Like the United States, the Soviet state was founded on the ideas and plans for the betterment of human, rather than concepts of identity and nation. Both were envisaged by their founders to be grand experiments, on the success of which the future of humankind depended. (39)

Wested is careful to acknowledge that there are many factors which distinguish the Soviet and American contexts from one another. Russia on the eve of the Communist revolution was overwhelmingly rural. Serfdom was not abolished until the middle of the 19th century– hundreds of years after the waning of feudalism among the British ancestors of the American revolutionaries. The Russian middle class was minuscule.

These important differences aside, the Russian/Soviet and American trajectories embody important parallels. Like their American revolutionary counterparts, Russian Communist revolutionaries– the Bolsheviks– inherited an old expansionist empire much as the United States developed out of the British Empire. Like their American counterparts, Russian Communists believed their version of modernity was a gift to the world.

In both cases the ideologies that justified intervention had developed from concerns that were formed in earlier centuries, under different regimes. For the Russian Communists, this meant that not only did they inherit a multicultural space in which Russian was spoken by less than half the population, but they also took over a state in which the tsars for at least two generations had attempted a policy of Russification and modernization of their non-Russian subjects. Many Russians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including some who became Communists, believed that their country had been endowed with a special destiny to clear the Asian wilderness and civilize the tribes of the East. (40)

On this foundation of parallel, if opposed, ideologies and of inherited presumptions of cultural superiority in an age of territorial expansion, Wested charts the development of the peculiarly Russian/Soviet version of this trajectory. Two elements are at the forefront of this discussion: 1) Soviet communism as a distinct version of modernity and 2) the Russian imperial inheritance. He concludes this discussion with an examination of Soviet interventions in the Third World during the Cold War.

The essence of Soviet ideology– Marxism-Leninism– was the belief in a class-based revolution that would end in a system of universal equality and justice.

While most Americans celebrated the market, the Soviet elites denied it. Even while realizing that the market was the mechanism on which most of the expansion of Europe had been based, Lenin’s followers believed that it was in the process of being superseded by class-based collective action in favor of equality and justice. Modernity came in two stages: a capitalist form and a collective form, reflecting the two revolutions– that of capital and productivity, and that of democratization and the social advancement of the underprivileged. Communism was the higher stage of modernity, and it had been given to the Russian workers to lead the way toward it. (40)

The Russian Empire at its most extensive (1866) in dark green. The lighter green indicates areas of Russian influence, not outright control.

In addition to this commitment to their ideology, Russian communists inherited a massive empire from their tsarist predecessors. Along with that inheritance, came many of the attitudes of superiority alluded to above. Russian territorial expansion began in the 16th century and reached its apogee in the 18th and 19th centuries. Under Peter I (d. 1725) and Catherine II (d. 1796), Russia acquired territories along the Baltic, took over Poland and Lithuania and much of the Ukraine, and acquired territories along the northern rim of the Black Sea from the Ottomans. They also advanced into Asia throughout this period and, to the north, took control of Alaska by the end of the century. During the 19th century, Russia conquered almost all the territories in the Caucasus and large swaths of Central Asia engaging the British in a rivalry (the “Great Game”) over this region throughout the century.

Wested criticizes those historians who would say that Soviet expansionism in the 20th century was just a continuation of Russian imperialism of the previous centuries. In fact, Russian imperial adventures suffered a series of setbacks in the early 20th century including the loss of a war to Japan in 1905 and a poor performance in World War I. When the Bolsheviks overturned the tsarist system, the Bolsheviks pulled out the war and disavowed many of the imperial arrangements made with other powers. But:

The Bolsheviks shared with the elites within the Russian empire a conviction that their country would eventually become the center of a new world civilization that would be both modern and just. Lenin believed that having been the first country that experienced a socialist revolution, Russia could do much to help revolutionaries in other countries… (46)

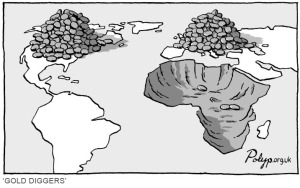

As the Soviet Union took root, institutions were built to export the revolution, most prominently the Communist International or Comintern, established in 1919. Lenin and his associates believed that the the capitalist countries were on the verge of defeating one another through imperialist rivalries for resources and markets. The Comintern was to be the mechanism by which communists around the world would set off anti-colonial rebellions.

Lenin was the master theoretician of the Russian Revolution but he died in 1924, too early to see its accomplishments and failures.

That task fell to largely to his successor, Stalin, who was just as committed to the ideology of communism but also as imperial and autocratic as his tsarist predecessors. Much of the story of Soviet Cold War relations with the Third World is a story of authoritarianism and condescension inspired by a distinctly Soviet communist missionary zeal.

That story will have to wait for another time.

![Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico [sic] and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. The caption reads: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you've got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!" Originally published on p. 8-9 of the January 25, 1899 issue of Puck magazine. The blackboard reads: "The consent of the governed is a good thing in theory, but very rare in fact. — England has governed her colonies whether they consented or not. By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world's civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves." Note the Native American reading a book upside down, the African-American washing the windows, and the Chinese figure outside.](https://insidethemiddle.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/school_begins_puck_magazine_1-25-1899_cropped.jpg?w=300&h=194)